Royal Palm Court

A. A. de Levine

The neighbors’ lions and horses are a dusty rose color with a high sheen. When the midday sun hits them, they glow pink. They hold stately ionic columns upon their backs, faces stoic despite the weight they carry. A porte-cochère, it’s called. That’s French.

Royal Palm Court is a sought-after address, as I’m sure you know. You can tell just from standing here by the gate, looking over at the lions. Our own front entrance is flanked by gryphons, their expressions serene as they look out over our lawn. Our house is larger than our neighbors’, a Model A versus their Model B. They have the porte-cochère, but we have a fourth bedroom, and an extra half-bath.

I am not sharing this to brag, as I have no need to. I am simply sharing a fact, for those who might care about such things.

My first wife pretended not to care about such things, to not be impressed by the houses and the lawns and the large front gate with an R and a P and a C all intertwined.

“What’s the point of a gated community,” she’d said, “if no one’s trying to get in?” She’d laughed. “It’s too much house for us,” she’d also say, often, looking around while drinking her morning coffee, or at night, the two of us in bed, the house quiet and dark. “Wouldn’t you prefer someplace… smaller? Cozier? A place we could make our own?” But this was our own, I’d tell her. It was our home, gryphons and all.

My first wife was not sensible, nor tactful, nor was she concerned with practical things. I cared for her, of course. But she was the kind of woman who called things “cute,” who spoke in baby-talk to dogs and cats. She thought the gryphons gracing our entryway were “cute,” too, but often accused me of wanting a porte-cochère like the neighbors’, of looking out over the adjoining property with longing. This was ridiculous, of course, and I would tell her so. I could have any house of my choosing on Royal Palm Court, and she knew this.

My father built these houses, his company creating fine communities where once stood only wetlands bordered by slash pine. My father, an intrepid man, had looked out over this barren land and had seen possibility. Endless possibility. And when I looked out over our lawn or the neighbors,’ I saw it too.

My second wife is much easier to please; she likes the things I like. Our values are shared. And I will make sure she is comfortable, that she knows this is her home, too.

After all, as anyone can see, this is a great house, with a double height foyer and a grand, double winder staircase. The kitchen features a breakfast alcove and walk-in pantry, a bar area and granite countertops. The appliances are all stainless steel, all top of the line. The living room is large, bright, with French doors opening out onto a courtyard. When my father drained the marshy land, he brought in good soil and massive, spongy rolls of Kentucky bluegrass. In lesser developments, you might see patches of crabgrass, unsightly and wild. But not here, not in Royal Palm Court. My father’s company is careful, meticulous. They planted fruit trees and bougainvillea and the namesake royal palms.

Of course, there have been setbacks here and there.

That is to be expected. There have been storms and disease, citrus fruit turning gray, bark splintering, odd smells rolling in from the surrounding wilderness. These things happen, Florida being Florida, the land being what it is.

I am clear-eyed about this place’s faults, of course. This is an area in flux! The land we’re standing on is all man-made, the dirt brought in from who-knows-where on what was once rivers of grass, with water snakes and garfish swimming through the brown water. The developers brought in new trees, invasive species to soak up all that water, to make the land dry and habitable for humans—and for us, a decorative lake along one edge of the development. I can see the irony, of course, of drying up marshland to build a lake. I can laugh about that! I have a good sense of humor, after all.

This all means, of course, that night here falls heavy and dark. We are far from the highway, far from commercial buildings and malls and hotels. It’s peaceful that way. This is how my father planned it. A man works all day, surrounded by toil and noise, and when he returns home, he wants quiet, tranquility.

My first wife did not understand that, but my second wife will.

They say a good marriage is built on communication, but that is…treacly, you know? A feel-good aphorism repeated by twittering morons. A good marriage, in reality, is built on calculated silence, on the empty and soundless spaces between two people.

And so, to keep the peace, to keep things tranquil, I do not tell my second wife about the mold.

The mold.

My wife first noticed it, just a few spores, in the hall closet where we kept our ski gear and other seasonal accoutrements. That’s French, again. She’d called me up to show me, visibly upset, near tears.

“Look,” she’d said. “Look at what’s happening in this house!”

The mold was unlike anything I’d seen before, I’ll admit. It was pink and iridescent, little globules clumped together in a wet-looking mass. Revolting, really.

“We’ve been breathing this in for who knows how long,” my wife said.

“Why were you fiddling with the closet?” I asked her.

She was evasive, curt. “I heard something.”

She insisted I call my father’s company to complain. “A rush job,” she said of the house, the street, the entire neighborhood. “People,” she told me, “were never meant to live here. This was meant to be undisturbed.”

She was not a respectful person.

The house had been a gift to us. My father had died, passing the house on to me, his only child. Royal Palm Court had been his life’s work, though unappreciated in his time. My father was a man with a vision, which is something my first wife could not understand. He saw families laying on green, green grass. He saw speckled light through swaying palm fronds, casting leopard spots on smiling, upturned faces. He saw white fences and rows and rows of shingled rooftops, pristine blue pools that were cool in summer and warm in winter. He saw that this place could be something more, a comfortable place. A tranquil oasis.

He was involved in every detail, every shingle and tile. The houses were elegant, built to impress. My father’s vision was becoming a reality. Families moved in, employed by local resorts. Water park owners, dentists, lawyers.

But then the storm hit.

Hurricane Adele, a category 5, ripped through the coastal land before heading deeper into the marsh, uprooting trees, peeling rooftops from homes, plucking telephone poles from the ground and sending them flying, hurtling across the dark yellow skies and through buildings and cars.

Seventeen people died in all, from nursing home residents to homeless veterans to a woman slammed into her bedroom wall when an albino alligator, already dead, was sent crashing through her unboarded window. People passed through the resulting wreckage like zombies, silently mouthing nonsense as they wandered through neighborhoods rendered unrecognizable: a Howard Johnson ripped from its concrete foundation, its signature pitched roof in pieces across the ruined landscape, a fiberglass manatee torn from the roof of a car dealership and sent flying into an elementary school.

My father’s dream lay in tatters across Central Florida.

He died soon after, in a rotting four-post bed within a house of his own design. This very house, in fact. His clouded eyes stared at nothing as he waited to die. I think the storm had sapped his will to rebuild, to fight against the marshy land in order to see his vision truly completed.

My poor father, dead before he could realize he was simply ahead of his time, a visionary whose fruits were not yet ripe enough to be harvested properly.

But I continue his legacy, still. When the area was rebuilt, including a fine resort with trellises and tearooms and an adjoining boardwalk better than before, new people came.

“Nouveau riche,” my first wife called them, dismissively. But shouldn’t everyone have a chance at the dream of home ownership, of comfort, of luxury, of a three-car garage and custom home theater system? I think so. And my father would agree. With the influx of all these new people with money to spend came shopping malls, a twelve-screen movie theater, an Olive Garden, a bowling alley and arcade, churches, banks, and the billing office for a university students could attend online.

The houses on Royal Palm Court—once condemned, once doomed to rot, once half-collapsed among the fetid water and crawling vines—were now revitalized, repainted, reroofed. My father’s company, with me now at the helm, added new architectural touches: the lions and gryphons and stone horses that so captivate its new residents.

I don’t think my first wife ever realized what a privilege it was to live in this model A home with its double height foyer. I don’t think she ever cared.

It seemed that all she could see, and all she would talk about, was the mold.

“Black mold’s what you’ve got to watch out for,” said the man who came by, and of course, he was right. He eyed the pink patches on the wall carefully. “This is probably nothing,” he said. He worked for my father’s company, so I know he could be trusted.

“See?” I told my wife. We watched, together, as the man applied anti-fungal spray to the wall. She walked through the house with a mask on, a flimsy thing with Hello Kitty across the mouth, making a mockery of this house, its stateliness, its cleanliness and its refinement. You would have thought we lived in a hovel by the way she carried on. Of course my father’s company brought out an expert to look at the mold, and of course they inspected it closely, cleaned it all up.

But my wife carried on, regardless. After the man left, she mixed vinegar and baking soda and scrubbed at the spot in the hall closet where she’d found the spores, every day for a week, on her hands and knees. She’d gotten rid of the ski equipment that’d been stored in that space, convinced it had been contaminated somehow.

“We never go anywhere anyway,” she said, as if all this had been my fault. Can I be blamed, really, for wanting to stay in a home so beautiful, a home that rivals most hotels, most resorts?

“It gets in deep,” my wife said. She scrubbed and scratched so hard, every afternoon, that she split a fingernail straight down the center. She removed the glove she’d been wearing and looked down at her hand. “That’s what it does. It gets down deep.”

I told her she was being ridiculous.

Eventually, I got her to stop cleaning, to stop scraping away at the spot on the wall, low and near the floor, where she’d first seen the pale pink spores. But, even after, she found ways to torment me, to hold the mold over my head. I would see the way her eyes shifted when she’d pass that spot, the way she’d glance over at the closet door whenever she walked down the hall.

I could see her, from the living room. Just standing there, looking.

“Stop it,” I told her. “I know what you’re doing.”

“It’s still there,” she’d say, over and over. Stubborn, like I said. Insistent, almost pleading. “I can feel that it’s still there.”

Sometimes I’d catch her looking up at the second floor landing while we were both in the living room, or craning her neck up at the ceiling while preparing something in the kitchen. State of the art appliances, and she was worried about mold. Just a little mold, already inspected by a reputable company.

It was a calculated stand, I knew, against all the things I loved: this house, my father, the picture of the life we could have had together.

I didn’t know why she acted this way. We had the house. We had enough.

We had loved each other once, deeply and truly. And, I confess, there is a part of me, deep in the marrow, that still loves and will always love her. She was impudent and set in her ways, but she was also charming, beguiling, funny. She was smart, too, sometimes offering an opinion so precise, so unique that turning to face her in those moments was like seeing her for the first time. Who knew, I’d always think, that she was capable of such a thought?

We really did love each other, the two of us in this house.

But things change. Time corrodes everything.

She pulled away from me even more. She began to form strange habits, staring out from doors and windows into the surrounding marsh. She would go out, sometimes, and lay on the grass, grass still wet with dew, so that her shirts became streaked with green.

When in the house, she kept herself covered, piling on sweaters, wrapping herself in blankets. We had not been intimate for some time, by then, but she became even more sensitive to touch, recoiling from me if I so much as walked near her.

And always, always, she would act like she was hearing something upstairs, something within the walls, something behind closed doors. She was always listening for something, but never listening to me.

It wasn’t always like this.

I don’t remember much of being young, I admit, and maybe I was one of those people who truly never was, but I do recall two moments, clearly and readily.

The first: being eight and peering through the car window as my father, and my mother beside him, drove away from the newly-opened Royal Palm Court.

“Hurricane Adele is on her way,” my father had said, and I remember picturing the storm as a woman, mad with sorrow, looming over the landscape, watching our little car drive off toward bluer skies, angry at us for leaving her.

The second moment: the first time I saw my wife. It had been just after another bad storm, a violent downpour that had left the dorm halls flooded and foul-smelling. She had been walking through the standing water in high boots, her face blank. I offered her a sweatshirt, dry and warm, and she looked up at me. And in her eyes, there was nothing. I can see it so vividly, still. And I think that moment, that very first moment, is when I loved her most.

I think of these two moments now, after everything that has happened. After discovering what my wife, my first wife… after seeing what she had been doing.

We had taken to spending the evenings separately. Gone were the days when we would read side by side or watch a little television together, the wild dark of the land seeming so distant, so far from us in our warmly-lit home with the newly-installed light dimmers and remote-controlled shades. And so I would often spend nights in my study, a small, comfortable retreat just off the living room, my door always shut against the sounds of a settling house and my wife’s footsteps upstairs, doing whatever it was that she’d do in the evenings. I had been working late that week, and so I’d fallen asleep at my desk, depleted. Such is life when a company is flourishing. Work begets more work! I’d remained there for hours, I suppose, eventually waking to a house overtaken by a silence I had not experienced since the moments before the hurricane, so long ago. It was an eerie silence. A calm of sorts, but too still to be comforting. Not tranquil. Not at all.

I called out for my wife and heard nothing. I ventured out from my study and into the tomb-silent dark of the living room. It was empty and it was warm. My wife, I surmised, had turned off all the climate-control options. A foolish woman, playing at some game. She would blame me for this, somehow. For a house that was too cold, then too warm. For ceilings that were too high to hold a family together, in her words. For mold that grew in a hall closet. For everything. I stood there, jaw clenched, growing more and more annoyed, considering all the things my wife must be thinking.

I stepped further into the dark. The humidity made the night feel like it was a living, solid thing, a thing that clung to wrists and shoulders. I listened intently as I made my way through the living room. Presently, the silence was punctured by a weak shuffling sound coming from somewhere upstairs, so I walked towards the staircase, passing the large wall clock in the kitchen. It had been stopped. It’s why everything is so silent, I thought. The humming of modern life, the droning of appliances, the soft ticking of clocks and watches, the beeps and chimes that form the constant, pulsing background noise of life in a suburb, had all fallen away, and now there was nothing. But why had she turned it all off? The power gone, the home silent. The expensive, reinforced glass of our house’s doors and windows were far too thick to allow in any sounds from the tangled wild beyond our own manicured yard, as was their purpose.

And then, upstairs, the noise repeated. Just the merest shuffle, the smallest little sound. I walked up the stairs, through the muggy dark, towards the sound.

I regret it, still.

I should have remained in my study.

I should have passed the night in dreams, safe in a different world altogether.

But I climbed the stairs. I walked out onto the second floor landing, to the hall enclosed by wrought iron, forming a balcony of sorts, overlooking the living room.

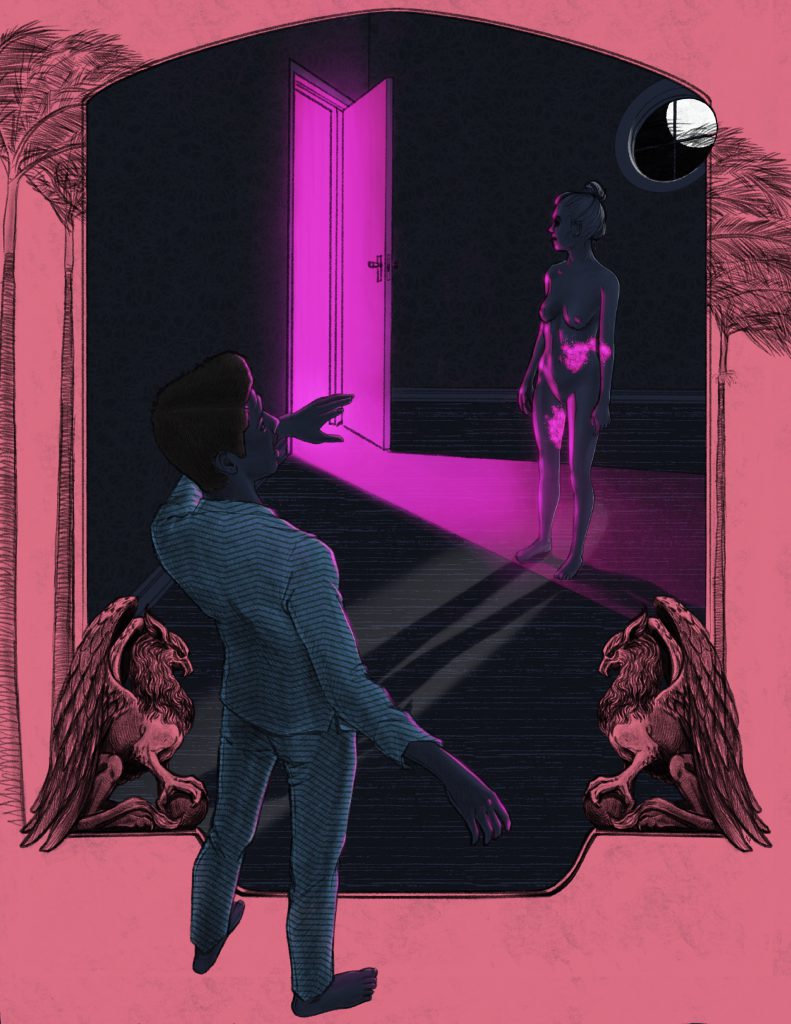

And there, in that narrow hall, on that landing, stood my wife.

She was naked, completely. Her ratty team-building t-shirt lay on the floor beside the old gray sweatshirt she’d borrowed from me when we first met.

Her nudity was shocking to me in its plainness. I had not seen my wife’s body like that in some time. It faced me, her body, but her face was turned away, staring into the open closet.

And then I saw what she had been hiding from me.

She was gray-blue in the dark except, I could see, for luminous patches of pale pink mold growing directly on her skin. On her thigh, the curve of her elbow, her belly. These patches morphed across the landscape of her body, expanding and contracting, the pustules beating as if hiding secret hearts within.

I was overtaken by panic, and the fear became so strong it doubled in on itself, freezing into numbness, into nothing. I could not move or speak; I could barely form my swirling thoughts into something coherent. I could only look at my wife, nude and shimmering, the light peeking through these patches of mold, this fungal entity that had overtaken her. She turned her face to me, then, and I could see, to my horror, that it had partially collapsed in on itself, that the fine bones and warm flesh on one side had been replaced by pulsating mounds of this… this stuff.

My mind was too far gone to remind my open mouth to scream.

She began walking towards me. She or it, this thing that was my wife, my wife who was this thing. Each step the thing took, shaky and jittery, seemed to shatter reality, seemed to push me further into madness.

I realized, suddenly breaking from the numbness, that I should step back and away, that I should shield myself, that this hand, this hand in the shape of my wife’s but that did not belong to my wife, this hand blooming and growing and moving and changing, could not and should not touch any portion of my flesh.

I screamed, then, and the scream was eaten by the darkness.

I moved away, walking backwards across the hall, one hand along the iron railing, precariously close to the top of the stair, the moon spilling through the porthole window above, a decorative little thing that I remember my wife asking about when we first moved in. “Why a window so high up?” she had asked me. She did not like that the ceiling was too high to clean easily. She never did understand proportion, elegance, decoration. She never would. And in that moment that silly woman seemed so far from me, that woman who had so aggravated me, and whom I had so loved. She was so many miles away from this thing that wore her face, this thing that had wormed its way into her body, that had been blooming, quietly, among her heart and lungs, this thing winding down her spine, softening the bone, eating away at her. This thing with its own private life and desire, completely unknown to me. This thing that had remained hidden, growing in the dark.

I saw, backing away, that this form could not hold its shape, that what was left of my wife, her outer shell, was crumpling inward, a house demolished, a house in ruin, tree roots turning a foundation to dust.

The mold spread fast, visibly, blooming in patches all down her legs, making it so that she could not walk and could only lurch and stumble towards me. The eye that was left on her face was unfocused and, yet, there was an intelligence in that one eye. There was still some aspect of my wife trapped within this rotting form, and it was…

It was afraid, I could see. Of me. Of me. It did not want to keep moving towards me. My wife, no longer at home in her own body, was trying to move away from me but could not.

“Stop,” I said, and my voice sounded small, child-like. “Please stop.”

The thing could not speak, could only open its mouth, a reflex, the tongue gone, the teeth shifted, the roof fallen away to all these peachy-pink globules, lit from within.

A tear fell down my wife’s borrowed cheek.

Trembling violently, I grasped at the wall, not wanting to fall and plummet to my death on these stairs or, worse, to survive the fall but only just barely, to watch, immobile, as this thing moved haltingly, shakily towards me, this thing that knew only how to destroy, to replace.

As the luminous thing, so full and blooming now, so replete with glistening spores lurched again toward me, I brought a hand to my face and, afraid, threw myself back against the wall, nearly losing my footing. The thing grasped at me and caught only air, falling forward into the dark, tumbling down the stairs and breaking apart with each step, soft and rotted through as it was.

I stood in the dark for a long time, breathing, waiting.

Finally, I made myself look down, to the foot of the stairs.

My wife, I saw, was no more. There were only strewn pieces of the thing that once held her.

And that eye…

I covered my mouth with my hands. The single eye remained open, the lid eaten away. And the eye, it looked up. It looked up along the length of the double height foyer, so that it looked at me, at me trembling at the top of the stair. That eye still held something sad, something broken. The eye looked and looked. And what it saw, it hated.

I watched until the eye could look no more, until the light within became extinguished. My wife, my first wife, became a mess upon the floor of our Model A home.

All was still in that dark, dank house.

It felt like an eternity, locked there in fear in the dark.

And then, all at once, the hum of life began again. The lights returned, and with it the ticking of clocks, the humming of the refrigerator, the cheery, rehearsed voices from the HD TV.

I looked across the house and then noticed, at the bottom of the stair, a stirring. The disparate parts of my wife—barely recognizable as her limbs, the hands I’d held, the birthmark upon her shoulder blade, the butterfly tattoo on her hip, a youthful decision made loudly and sweatily on Spring Break with a loud, sweaty knot of friends whose closeness would not make it into adulthood—these pieces crept, as if through an intelligence and will all their own, back together, once again forming a whole. The mold, the pulsating pink swatches, diminished in size, their glow fading as the mess at the foot of the stairs became a body once again.

My wife, again.

But not.

A new wife, blinking in the dark, gathering her bearings and then turning her head, painfully, to stare up at me.

My new wife.

A gift, I could see. A chance to start anew.

A gift from the house.

And as I take her out with me onto the front lawn, a new day’s sun rises. I turn her, gently, towards the neighbors’ lions and horses. I point them out to her. Dusty rose with a high sheen. When the midday sun hits them, I tell her, they glow pink. They hold stately ionic columns upon their backs, faces stoic despite the weight they carry. A porte-cochère, I explain to her. That’s French.

Do you see?