Let Shadows Slip Through

Kali Napier

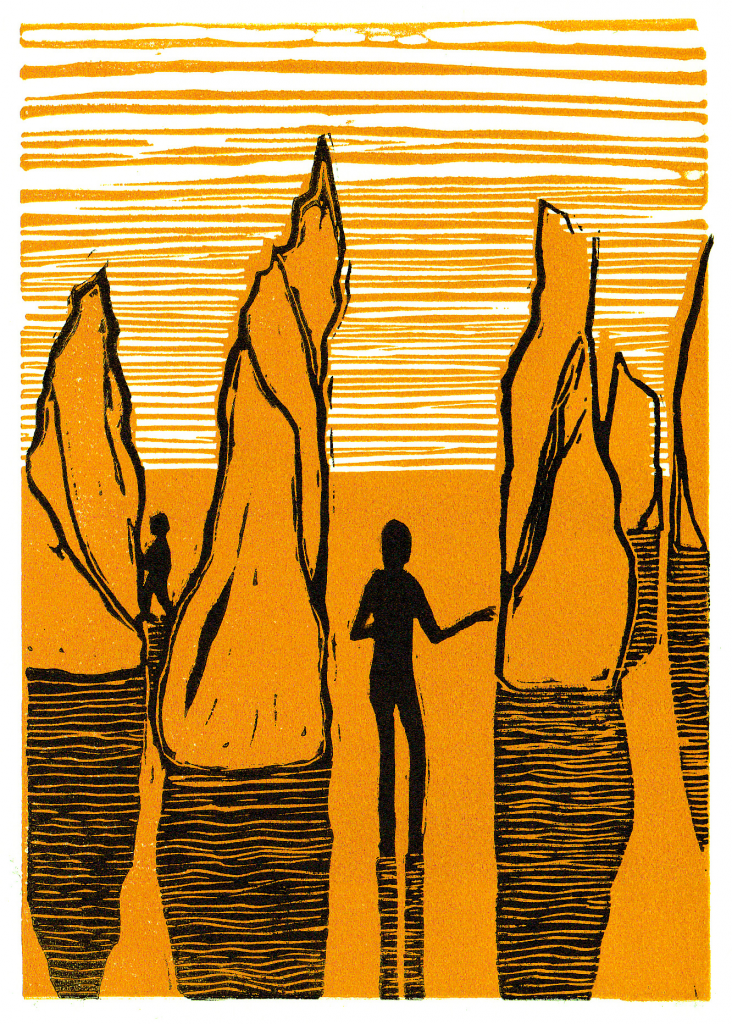

Illustration by Heather Parr

The Pinnacles are an hour behind us but I’m still jittery. I check on him in the rear-view mirror. He’s okay, bent over a picture book, his dark thick hair—like mine, not his father’s, which is red and thin—hanging over his face.

‘Billy,’ I say, because I need to see his eyes, ‘How’s it going back there? Mummy loves you,’ I add as I always do.

He looks up. I get my smile. ‘Love you, Mummy.’

I breathe out. But my left knee trembles. Sweat snakes down my calf. Maybe I lied to the petrol station owner at Bullsbrook.

‘How’s the humidity?’ he’d said, mopping his brow with his hairy arm while he rang up the packet of fruit lollies and the tank of petrol.

‘I’ve been living in Brisbane for three years,’ I’d said. ‘This is nothing.’ He was the fourth person today to comment on the weather. How can I have changed so much physically? Emotionally and psychologically, I can understand.

We stopped at the Pinnacles. Billy clambered over the rocky outcrops. Wind buffeted my ears, made snake trails across the landscape. My heart lurched each time I lost sight of him, the pocked stromatolites metres high, stark against the shifting dunes.

I told him off for scaring me when he reappeared. ‘You might fall.’

He did fall. He cried.

He disappeared again. Shadows peeled from the heels of the limestone formations and rippled in the sand. I thought one was a man. Billy cried out and I jumped.

I brushed grains from his hands, cupped them as I washed them with water from the bottle in my handbag, and blew. He was okay then. As we walked to the carpark, the outlines of the few gums, the toilet block, the white Falcon seemed to separate, to let shadows slip through.

Just heat haze, I told myself. But I clicked the key-remote with a look over both shoulders, flick-flick. Only my funhouse-mirror shadow next to my child’s. Nobody else here.

My heart barrelled one hundred and ten kilometres an hour up the highway, one hundred and thirty when I saw a flash of light glint off a windscreen far behind me.

The Caltex station at Dongara appears ahead of us. I’m calmer. Probably because Dongara means forty-five minutes until we’re home. The first time in three years. The Caltex and the bakery that makes the best meat pies slide past.

I take the tight turn into the S-bend too fast and careen, wheels skidding. Billy screams as his head knocks against the edge of his booster seat. I pump the clutch, take it down a gear, grip the steering wheel until we’re through to the straight.

It used to be intuitive, holding the inside curve steady at one hundred.

He’s whimpering now.

‘We’re right. We’re right. Don’t cry.’

‘Please, stop. Stop.’

I look at him in the mirror. His face is blotchy, tear-stained. The aircon doesn’t work in the hire car.

‘Okay, Mummy’s stopping.’ I pull off the road. To regroup. I hadn’t even seen the sign for the S-bend. A few hours of driving under the saturated blue sky and things like signs and bleached scrub tend to merge into each other.

I get out, arch my back, face to the sun. The air burns, frizzles my lungs when I breathe it in. I’ve missed this, oh, I have missed it so much. This is who I used to be, before my ex moved us to Brisbane. It was only supposed to be for a year. Then it became three. Then a life sentence when he took me to court so I couldn’t bring my child home.

I have ten days. I have to make it count, so that Billy doesn’t forget where he comes from until I can next afford the trip over.

He releases his seat belt, climbs out.

‘Don’t go off. We’re not stopping long.’

Billy kicks at the tyre. He is four. My counsellor says he might have been set back developmentally because of the stress his father has put us through. ‘No, don’t want to.’ He’s sniffling, smacks the door. Recoils. ‘Owwww, too hot.’

I touch the handle, the metal stings like a belting. I’ve forgotten this. Blisters from concrete pavers, buckles, white sand at the beach. It’ll take the top layer off.

I pick him up, splay his legs on my hip as I walk up and down the soft bitumen. Our skin is sticky where we meet, and if I could, I would fold him into me. I turn and pace again.

The brown tourist marker is faded, has a few dings and someone’s scratched I WAS HERE across the arrow. The fork-and-spoon and bed symbols for the Hampton Arms. Mum’s mentioned something about the tea room there, something that happened, but whatever it is was lost in everything that’s gone wrong this past year.

‘Are you hungry?’

He lays his head on my shoulder, nods.

‘Just five more minutes in the car.’ I spread my fingers out. ‘You can do that, can’t you?’

*

I park in the shade next to a graffitied yellow minivan with Victorian plates and pray the tea room won’t be noisy.

Around the courtyard are wooden pub benches and folded down umbrellas, and cacti spilling from pots. But I can’t see a soul. I clench Billy’s hand twice, our code for ‘I love you,’ as I follow the limestone walls to a latticed enclosure. Every door shut and padlocked, except one.

I’m heading towards it when a voice comes from behind me.

‘What can I do you for?’

The man’s wiping his hands on a tea towel. He’s late fifties, grey hair, in navy stubbies and a dirty white t-shirt, worn black flip-flops.

‘Sorry, I thought you were open.’

I glance up to the windows of the first floor; the hotel rooms closed years ago. A bed sheet for a curtain flaps in one window.

‘Are you open?’

‘Yeah, go on through,’ he says, and ushers us ahead of him.

I keep Billy close, glancing over my shoulder at the man. Feels like crossing a carpark at night with my keys between my fingers.

The tea room is empty. Four tables covered in vinyl cloths, with salt and pepper shakers, serviettes and a sugar mill on each. A stack of magazines to read. I use Billy’s hat to dab at the sweat on my brow then hook it over the corner of his chair, which scrapes the lino when I push him up to the table.

‘I’ve got a fan I can bring in, if you like.’

‘Thanks. If it’s no trouble,’ I say.

When the man goes, Billy slips down from the table. I sigh but can see what’s caught his attention. There’s an adjoining room. I follow him. The lights dim, filtered through wire screens thick with dust. Dust on almost every surface, in fact. His yellow shorts are filthy where he sits on the floor to pull out a shoebox of old toy cars.

It’s quiet, apart from the clink of metal as he rattles the cars over the wooden floor boards, crashing them into each other.

‘Ka-boosh.’

I glance at the framed sepia photographs on the walls. Greenough Hamlet of about a hundred years ago. Iron farm implements, kettles, an old packet of Bird’s Custard, sit undisturbed on a large dresser. Small roadside museums used to fascinate me when I wrote for the Geraldton Guardian. You wouldn’t think there’d be much traffic passing by, but their hopefulness would show in the presence of a guestbook.

I frown.

Someone drove that graffitied minivan here, the one I parked next to. Why did I park so close? All the space in the world. Where are they? You can’t get through the dunes to the beach; the scrub is thick, and only a crazy person would go for a walk in the middle of nowhere in the heat of the day.

The man clears his throat behind me. Sneaking up on me again. And he’s blocking the entry to the tea room.

‘Can we make it takeaway, please? Two ham and cheese sandwiches.’

‘I brought the fan.’ He tilts his head, looks at my son in the corner playing with the cars.

‘Billy.’ I step between him and the man. ‘Pack up, it’s time to go.’

‘I want to play.’

‘You can play when we get to Grandma’s,’ I snap, and immediately regret it. I don’t like strangers thinking I’m a bad mother. I don’t like people who know me thinking it. It’s not Billy’s fault. But I’m so tense, he easily pushes me over the edge. I overcompensate every time, buying him Lego or icy poles, cuddling, telling him that I love him, that he’s part of me, like an arm. But the people who don’t matter don’t see that. They like to stand and tut, make faces.

‘I’m sorry,’ I say to the man, so he doesn’t make a face too. ‘I’m tired. We only got into Perth last night. It’s a long flight from Brisbane.’

‘Ah, well. You just relax. Sit in front of the fan in there while I make you up those sandwiches, and the boy can play some more.’

‘Will you be okay?’ I ask Billy uncertainly. Even though I’ve been sitting and driving all day I just want to sit some more. On my own. Just for a bit.

He nods without looking at me, driving his cars in a figure eight on the floor.

I wait at our table, pick up a three-year-old copy of People’s Friend magazine stamped with ‘Property of the Hampton Arms.’ But after a few pages of cramped text, my head swims and I put it down to pull out my phone. I can manage small grabs of Facebook.

I tap on a few icons with no success. A black spot; there’s no reception. I can’t remember what time we arrived but it must be at least fifteen minutes since the man disappeared into the kitchen.

I roll up the magazine, drum it on the table as I wonder if we should move on.

The scrape of my chair echoes when I get up, and I’m thumped in the chest—by something I can’t see, or hear.

I run into the silent museum room.

My child is gone.

Everything atomises, slamming me like a shock wave.

I scream his name along the darkened corridor to the kitchen where nothing’s switched on, thunder up the stairs but the door at the top level has boards nailed across it. I bang my fists against them, realise I’m clenching the tightly rolled People’s Friend in one hand. ‘Billy!’ I take the stairs down two at a time, stumble, turning my ankle as I emerge into the glare of sunshine. I shield my eyes with the magazine, limp through the empty courtyard, screaming, ‘Anyone? Help me! My son’s missing!’

The old man doesn’t come.

No one comes.

Billy’s not in the carpark. The one straw. The one straw I’d clung to was that he might have snuck out here.

I fall to my knees, whimpering, as grief crashes over me. It’s like the magistrate’s decision all over again. But this time, I’ve lost my baby completely.

The graffitied minivan is gone.

*

I jab my finger on the volume button of my phone, the other hand steadying the wheel, alternating with gear changes, as the metal sails on the highway welcome me to Geraldton.

‘Officer, I’ve already told you. Sixteenth of August 2009. He was born here, at the Geraldton Regional.’

I drop the phone to the passenger seat as I go through a red light. I’ve been going over one hundred and sixty; another misdemeanour won’t matter as I’m heading to the police station up ahead.

I park on the kerb, arse hanging over the road, grab the phone and my handbag. I don’t care that I’ve left the car open, and hurtle past two police officers coming through the glass doors.

‘This is a police station,’ one cautions me, like I’m some kind of idiot.

My throat constricts. There’s someone talking to the desk sergeant, who glances in my direction, before returning to the German windsurfer who’s complaining loudly that his wetsuits have been stolen.

‘Please?’ Tears roll down my face. ‘Please?’

The desk sergeant disappears, and comes out the side. ‘Do you need emergency assistance?’ he asks.

I grab his sleeve, nod. ‘I phoned…my son…he’s missing.’

My sight is narrow, like binoculars, and I don’t see where the other pair of arms comes from, but I’m taken into a room. I lift my face from my hands. A plastic cup of water is on the table.

I sip. It tastes of blood. Think of Billy. Convulse.

‘Do you have ID on you?’

A young, blonde and female officer. Good. Men never believe me, always take his side. She’s enough to give me hope. I take a deep breath. I must be rational, pass her my driver’s licence.

‘Mrs Kane, is it?’

‘No. I mean, yes, I was. I’m separated. Sarah Armitage now.’

‘Ms Armitage, I’m Constable Joanne Trotter. I’ll need some details from you.’ She sits across from me, sets down a notepad and pen.

‘Thank you, thank you.’ I brace myself, palms flat on the table.

Her hair is done up in a bun. There are three studs in her right ear, two in her left. I look her square. She will believe me. She has to. Part of me knows that she’s here because they always give female cops the weepers, the kids, the hysterics. The victims of domestic violence.

‘Can you tell me, in your own words, what happened to your son?’

Who would be putting words in my mouth? The taste of blood is still in my mouth.

‘We stopped at the Hampton Arms for lunch. He was playing while the owner went to make our sandwiches.’

‘The owner? Did you get his name?’ The officer puts down her pen.

I shake my head. ‘I didn’t see him again. Not even when I was screaming for help when I lost Billy.’

‘You lost him? How?’

I clench my fists, press them together. ‘Not like that. I was in the next room, and everything was taking too long and I couldn’t hear anything. And when I went to check on him—he’d only been a few metres away from me, I swear—that’s when I discovered he wasn’t there.’

‘A few metres?’ She picks up her pen, checks her watch, and scratches notes on her pad. ‘Could he have wandered off when you weren’t looking?’

‘No!’ She looks up sharply. I lower my voice. ‘No. There was only one door to the room. I was right there in front of it. I checked the place out—but everywhere was bolted or blocked off.’ I turn my hands over, release the tension in my knuckles. Bleeding half-moons cross my life lines.

‘Okay. Ms Armitage, can you tell me where your son’s father is?’

I grit my teeth. ‘He’s in Brisbane. He’s got nothing to do with this.’

Cold sweat runs down my spine. They think Gordon has kidnapped his own son. That’s usually the case in these situations, isn’t it? He’s an arsehole, but he wouldn’t do this. Would he?

This is exactly what he would do.

I squeeze my eyes shut.

Constable Trotter lays her hand on mine. I jolt.

‘We’ll give him a call.’

I nod, scroll through my contacts for his number and pass it to her. I need to know it wasn’t him.

When she returns, there’s another officer with her and I shrink. He looks like Gordon’s lawyer. All swagger, no compassion. Doesn’t care about destroying a life, he gets paid either way.

‘Mrs Kane,’ he says. Neither have sat down.

‘I’m not—’

‘Sarah Kane,’ he continues. ‘We’re holding you for questioning on suspicion of violating custody orders for your son, Billy Kane.’

I punch my fists into my temples. I can hear keening. I don’t know if it’s inside or outside of me. No-o-o-o-o-o-o-o-o.

Trotter grips my wrist. It doesn’t feel kind; it hurts. I’m weak as water, no strength to struggle. ‘I’m…’ gasping ‘…his mother.’ Sobbing. Shuddering. ‘You don’t understand. There was a minivan.’

‘Your husband’s emailed the consent orders. You were considered a flight risk in court and emotionally unstable.’

Only because the magistrate believed his lies. Because he’s a man. They’re all in it together. I can’t bring myself to look at the male officer.

‘He’s done this. I know it,’ I say to Trotter. ‘Maybe not himself. He’s hired someone. What about the man at the Hampton Arms? Gordon’s a Freemason…’

Trotter lets go of me, turns away. Please look back. Please believe me.

‘Ms Armitage,’ Trotter looks back, chews on the inside of her cheek, head bobbing on her neck. ‘The Hampton Arms was razed last year. The land has been on the market ever since.’

I was there. I grab my handbag, but it falls, spills its contents. There is no People’s Friend, no “Property of the Hampton Arms.”

‘No!’

I hold my hands like claws before me, streaked with ash.

The male officer’s got me pinned against the wall in seconds.

I think of Billy, disappearing between the limestone formations of the Pinnacles.

I think of him kicking the tyre, burning his hand on the car door.

I think of my boy playing with toy cars in a sea of dust.

They’ll never find my son.