I’ll Bring It In

Rebecca Parfitt

Old Proverb

Cate watched the clean air-dried bedsheets become soaked and heavy in the rainstorm. There was nothing she could do about it. She couldn’t move for her baby, Esme, suckling at her breast. Her living room overlooked the shared courtyard in her block of flats. There were no plants, no shrubs, nothing grew from the concrete, just rows of washing lines. She knew her neighbours only by their underwear, the size of their trousers, how many pairs of socks they hung up and the way they organised their colours. These neighbours always seemed to know when the rain was coming because when it was too late and she had only just looked up from what she was doing, their clothes would have vanished and hers and Esme’s would be the only ones left on the line. The cloth outline of the pair of them, mother and daughter: sleepsuit and floral dress hanging together, soggy. She wondered what her neighbours thought of her—the abandoned washing had become a habit. She always washed her clothes with good intentions—to bring it in dry on the same day she put it out. But since the baby had been born she had only one hand free at a time—if that.

The summer had been a rainy one with many storms. This one had passed through quickly and the hilltop beyond had become visible again. Everything came out of the shadow glistening wet in the sudden sunlight. The rain put a stretch on the line. With the added weight of rainwater Cate’s dresses were elongated slim-limbed versions of herself. The washing would have to stay there overnight till the morning to dry. No point bringing it in now, she thought.

At tea time there was a knock at the door. It had been a while since Cate had heard that sound. The baby was sleeping in her Moses basket so Cate was free to answer it. She peeped through the spyhole. There was a woman she’d never seen before wearing a red tie-dye dress. Her long blonde hair looked slightly damp, caught in the rain. She opened the door: “Hello?”

The woman was agitated, ‘Your washing is still on the line. Aren’t you going to bring it in?’

Cate thought this was rude. ‘Oh no,’ she said. ‘I’m going to leave it overnight, it’s soaking wet from the rainstorm. I’ve nowhere in here to dry it.’

The woman just stared at her.

‘Ok?’ Cate said, poised to shut the door. But the woman didn’t seem to want to move.

‘Don’t leave it on the line,’ she said.

‘I’ll leave it where I please,’ Cate replied, and shut the door.

Almost instantly there was another knock at the door. Cate waited a few more seconds. Esme began to cry. She looked through the spyhole, the woman was still standing there. What does she want? I am not going to bring my washing in, I am not. Another knock. Esme’s cry was getting louder. Cate shouted through the door, ‘I appreciate your concern but can you leave me be? My washing needs to stay where it is.’

Silence.

She looked through the peephole again. The woman had gone.

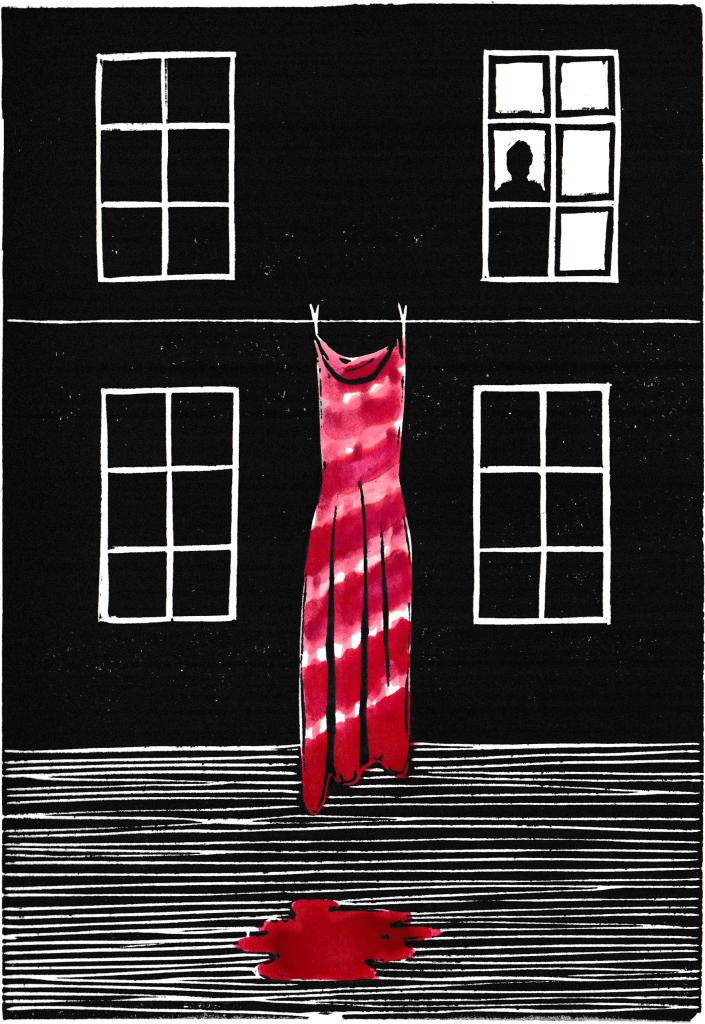

The next few days passed without incident and Cate did not see the woman—she had brought her washing in, after all. But today Cate noticed the only thing hanging up in the courtyard was the woman’s red tie-dye dress. The day promised humidity and rain and nobody else in the block had chanced it.

Throughout the day Cate came to her seat overlooking the courtyard to feed the baby. The dress remained there, two pegs clipped at the shoulders. It looked dry enough. She wondered why it was still there after all the fuss a few days ago and the woman’s persistence to have Cate bring her washing in. Why had she now left hers? Just one piece hanging on Cate’s allocated washing line. Why wash just one piece? How uneconomical. The other neighbours would be tutting from their net-curtained windows.

Cate could not stop thinking about the woman: the way her hair had a dampness, the faint scent of patchouli and something else, perhaps sweat or a slight mustiness; the insistence, the rudeness of her imposition. Of course when she had put the washing out she had perfectly good intentions for bringing it in. But things being what they were she had not managed it.

At around 4 p.m. it rained, and the dress got wet and hung limp. If only she knew which flat the woman lived in she would go round there and tell her she’d left her dress out. The colours had run right through each other and the tie-dye pattern now looked fleshy. There was a pool of vivid red beneath it. The image was startling: the dress looked as though it was bleeding. Perhaps the woman had gone out for the day. Or maybe she’s gone away and forgotten, Cate thought, turning her attention back to the baby who was making quiet gurgling sounds. Going out was something Cate had not done since the baby had been born—she ordered all her supplies online and got her fresh air in the communal yard. ‘The yard is far enough for me,’ she told the midwife. ‘I’ll go out when I’m ready.’

She recalled the midwife asking if there was anyone she could call.

‘Yes,’ she said, ‘but I don’t need them.’

The next morning the dress was still hanging out on the line. Cate decided she would bring it in herself.

She strapped the baby to her chest and went outside into the sunshine, into the open air. She felt her limbs stretch, her body crack back into place as she descended the stairs into the courtyard. She stopped to look up at the blue sky above her—framed on three sides by the building. One day I’ll get out there, she thought, then reached up to pull the stiff sundried tie-dye dress off the line. It held straight, as though a piece of painted paper in her hand.

She went from door to door, knocking. Looking for the woman whose dress it was. But nobody was answering. Each door was a blank face.

Cate liked the quiet, liked her isolation. She wouldn’t go back, not ever. Now it was just her and little Esme. And the damn dress. She adjusted the strap on the baby sling, which was digging in. The baby is getting so heavy now, she thought.

She reached the last flat in the block, directly below her own, and rang the doorbell. There was a light on and she could see through the net-curtained glass front door. At last a shadow, then a voice, ‘What do you want?’

It was her. Cate was sure of it.

Cate slowly bent to the letterbox, ‘I have your dress.’

Silence.

‘At least I think it is. You were wearing it the other day. You know, when you came round. About my washing.’

‘Post it through.’ The voice came sharp through the glass.

Cate pushed the letterbox open and began to feed the dress through very slowly. She felt the pull of the woman on the other side and then the letterbox snapped shut. The woman’s outline disappeared down her hallway.

Ungrateful bitch, Cate thought.

Cate ran her hand across her clothes in the wardrobe. Her hand felt something fleshy—as if she had just brushed against an arm of another person. She stepped back. Her breath caught in her throat. She carefully retraced her fingertips over the arms and legs of the clothes in her closet. Nothing. The only other flesh in this apartment was her baby’s soft body. She ran her hand back across the shoulders of her hanging clothes. The rack swayed a wave of colours and materials. No flesh. I’m tired, she thought.

She picked through her clothes reminding herself of the pieces she loved and treasured, held them up against herself and looked in the mirror. Sighed. Having given birth a few months earlier, very few of them would fit now. Her body had been rearranged by pregnancy and childbirth. She wondered if she would ever shrink back, slot into herself as before. But like everything else in her life her body was irreversibly altered. She had stepped across the threshold of motherhood and, as in a fairy tale world, the doorway had sealed up behind her and she would no longer have the ability to return to her old self. Nothing will ever come after this, she thought, as she placed a blue silk dress back on the rail. Esme will probably wear this next. It is just me and her now. She heard a cry from the sitting room. Feeding time. This is my life now, she thought, repetitious: cradling the baby and holding her to her breast over and over; wiping, folding, buttoning, soothing, stroking. These are the movements that shape a person, that make their edges soft or sharp.

As Esme suckled, Cate looked out at the courtyard. There was more washing on the lines blowing about in the bright sunshine: floral dresses, shirts and t-shirts. Funny, there are no children in this block, she thought. I have never seen any children’s clothes hanging. Just my own daughter’s sleepsuits.

The floor of the flat was vibrating; the washing machine was on its final spin in the kitchen. The basket was ready to load the clothes into and take outside. Cate loved hanging the washing, it was a pleasure to straighten them onto the line. The machine slowly unwound its spin and came to a stop. Esme had fallen asleep. I’ll leave her up here, Cate thought, I’ll only be five minutes.

She put the washing from the machine into the basket and pulled the door behind her and went down the concrete stairwell in her slippers. She passed her neighbours’ washing to her own line. Took in a deep breath of clean air and squinted up to the sky. She pulled down the peg bag and started to hang Esme’s sleepsuits, sticking pegs at the toes. The washing billowed in the wind, duvet covers ballooning in parcel shapes. The courtyard door slammed shut in the wind. I am doing normal things again. I can hang my washing out the way I like with the pegs at the toes, not at the shoulders. But this was a glimpse of her past she shook away with the towel she was hanging. This is my normal, she thought.

Task accomplished she went back upstairs clutching the empty basket, wedging the courtyard door back open. She placed the basket back in the kitchen. The kitchen tap dripped. She tightened the tap and went to the window to admire her small pleasure. Then she saw the woman with the tie-dye dress standing below amidst the washing. She had no washing of her own—there was no basket. She was simply standing there as the clothes billowed backwards and forwards in the breeze. She was probably enjoying the scent of the air. Then another neighbour appeared, unpegging her dry clothes from the line. She did not stop to speak to the woman with the tie-dye dress and the woman with the tie-dye dress kept her back turned to the neighbour. Cate became distracted by the dripping sound again. The kitchen tap splashed. Damn, I need to change the washer. When am I going to manage that? At this moment the baby woke up and all her thoughts dissolved into the pattern of soothing the baby’s cry.

Cate forgot to bring her washing in.

Later that night she watched it uneasily: towels, her nightdress and the little white arms and legs of the sleepsuits floating out there in the darkness.

When Cate drew back the curtains the next morning the baby’s clothes had gone. Her nighty was still flapping about but the sleepsuits had gone. Cate gasped fucker, in a half whisper to herself. Someone’s taken the fucking baby clothes. She’s taken the fucking baby clothes. Cate paced about wondering what she should do. She couldn’t just go marching down accusing but she knew in her gut it was that woman.

At noon there was a knock at the door. Cate smiled to herself, I knew it. She gathered her composure, walked to the door and peeped through the spyhole. She opened the door and before she could say anything the woman said, ‘I found them strewn about, must have blown in the wind. Thought I’d bring them up to you.’ She handed over the bundle of clothes.

‘There was no need,’ Cate said icily.

The woman seemed not to notice her tone and asked keenly, ‘How is the baby?’

‘Fine. Asleep. I must get on.’ Cate shut the door before anything more could be said.

The sleepsuits were dirty. Cate flung them into the sink. Fucking woman. They were clean when I hung them, she muttered under her breath. She squeezed detergent on them and ran the hot water tap, making a foam. She took a plastic brush and scrubbed. Fucking woman. How dare she. She smacked the sleepsuits against the side of the sink. She pummeled them until her hands were red. She wanted to get any trace of that woman out of the clothes. She couldn’t bear the thought of those skin cells touching the skin of Esme. She wanted to make sure of that with her own bare hands.

‘Sshh, darling,’ Cate soothed. Esme was crying. Cate peered through the window. This had become as much a part of her daily routine as the feeding had. Not an hour would pass now that Cate didn’t check the view of the yard as her washing dried. She had seen nothing all morning but the washing drying in the breeze. Then she heard the familiar sound of the courtyard door opening and there she was, the woman in the tie-dye dress. She walked towards Cate’s washing line, stopped and carefully lifted the corner of one of the dresses and sniffed. Then she went along the line and did the same with each item. Cate wanted to tap on the glass, do something to stop her. But she didn’t want to bring attention to herself, she didn’t want to upset the baby further. So she just watched. This woman is violating my clothes, she thought. Cate wanted to call someone to explain this. But then again, she didn’t want to seem like she wasn’t coping. Would this even make sense? She didn’t want to add another kink to her list of anxieties. She needed to do her washing, she needed to hang it up to dry outside in the fresh air; in the sun. This activity was good for her and was good for the baby. Did this woman even know what her actions were doing? She stopped herself for a second and thought: perhaps I am overthinking. Perhaps.

The washing machine was on a final spin and wound and wound and wound and wound. Cate was irritated by the noise: the ringing sound that it made and the vibrations on the floor. The second load of the day. If she could just get this done she could relax, have a nap maybe, if Esme would allow.

And then it came, the sound she knew would come: the knock on the door. Carrying Esme she looked through the spyhole: the woman in the tie-dye dress. Cate took a deep breath and opened the door.

‘Yes?’

The woman said nothing. She looked tired. She just stared at Esme, who stared back.

Then after a moment she said, ‘I’m missing some clothes.’

‘What kind of clothes?’ Cate asked. The woman stood there, just staring. ‘I’m about to sort my washing out—I’ll have a look for you, if you tell me what’s missing?

‘A dress. Puffy sleeves. A bow,’ the woman said vaguely.

‘Ok then.’ Cate smiled, one hand still on the door catch about to push it closed. ‘I’ll let you know if I find it.’

‘Ok.’

She closed the door but stayed behind it watching the woman through the spyhole. She was staring at the closed door, motionless, for a good few seconds and then she turned and walked away back down the corridor.

Cate held Esme very close. She could not shake the sense of unease. The proximity of the woman felt as though she was closing in on her. Her presence was larger than her form. Permeating the space with a sense of misery Cate felt she had to scrub from the walls and floors.

Cate kept up her hourly checks of the courtyard but a week had now passed and she had not seen the woman at all. Autumn was approaching. The September air had a crisp edge to it. Cate loved this time of year. This was usually when she felt most at peace. She thought perhaps she was ready to go outside. Out of these walls and down the street, into town. Like ordinary people she would go into town. But what would she do there? She imagined going to a café and getting a coffee and sitting down and drinking it. That was what normal people did. Normal people pushed their babies in prams and went to get coffee. The health visitor would say, ‘It is time. Go and do something normal.’ In the courtyard Cate hung Esme’s little sleepsuits by their toes, little upside down baby flags fluttering all colourful in the wind and sun.

Esme was wrapped up tight in the sling. Cate was ready to go out. She strode with purpose out onto the street. Walking to town. Walking with purpose with the baby sleeping in the sling. But she couldn’t help but notice how the windows of the houses stared out at them. She got a few streets away and had to stop. ‘I don’t feel so good,’ she said to Esme. They were half way between town and the flat. She thought, if I go on, I’ll have further to get back. If I go back? If I go back? If I go back? She took one more step towards town. The sky had clouded over. I forgot my umbrella. I’ll get soaked. Esme will get soaked and she will get a fever and then I will be accused of being a bad mother. I don’t know what to do, she thought in desperation. Then the sky opened and poured. Cate ran across the road to a bus shelter. Esme was still asleep, tucked in, warm by her chest. ‘Let’s just stay dry here and then we can go home.’ She kissed the top of Esme’s fluffy head, breathed in her sweet scent.

The rain passed quickly. The sun came out and it felt suddenly hot. Be honest with yourself, she thought, this is all I can manage today but it’s better than yesterday and the day before that. So congratulate yourself for getting this far. She’d read about pepping yourself up with little mantras: Well done! She heard the patronising voice of her health visitor.

Now she could see the flats from the end of the street. Home. As she got closer she saw a glimpse of the washing lines and the woman in the tie-dye dress through the railings to the courtyard. Something wasn’t right.

Cate froze on the spot and watched as her neighbour carefully hung one of Esme’s tiny dresses out.

The woman spotted her and turned to wave, the sunlight catching her blonde hair in a halo. An angel of mercy, Cate thought, look at her, she thinks she’s being helpful. Cate’s heart was beating in her throat. She wrapped her hands round Esme’s little fists tightly. She wanted to push the woman away. She wanted to rip the clothes from her.

As she approached, the woman smiled cheerily, ‘The rainstorm came so fast—I saw you leave earlier. I didn’t want the baby’s clothes to get wet.’

Cate pressed her lips together in a tight smile to mask her fury. ‘There was no need,’ she said.

The woman’s focus turned to Esme, who had just woken, peering out from over the top of the sling. ‘Aw, she’s smiling at me.’ She leaned forward to touch her.

Cate’s grip tightened around Esme’s fists and she stepped back. ‘Don’t,’ she snapped. ‘Don’t touch her face.’

The woman’s hand withdrew. Her face darkened in the shadow of a sheet suddenly blown across by the wind. The woman turned and said, ‘You should put fabric softener in your clothes. It’ll be softer on the baby’s skin.’

Cate felt a sting in the way the woman said it—another criticism of the care of her daughter. She felt the woman’s judgement descend on her. She crumpled under it—all of her inadequacies came at her at once.

‘She’s fine thank you.’ Cate broke eye contact and scanned the line. ‘That’s not mine.’ She pointed at a little, faded red sleepsuit.

‘Isn’t it? Well, it’s still a bit damp, I’ll leave it to dry here a little longer.’ The woman smiled and drifted off inside.

Cate stood in the courtyard for a moment watching the washing blowing up and about in the breeze trying to quell the shaking, trying to stop the swell of fear and doubt growing inside her. This washing is my life now, she thought, and I can’t even get this right. How endless and endless this domesticity has become. It’s not me, it’s not me—even a stranger can see that. She suddenly felt guilty for rebuffing her neighbour. Hadn’t she been helping? Looking out for her, after all? I should be more grateful. Perhaps I should get some fabric conditioner. Perhaps the clothes are a little too starchy, drying out here in the sun.

Cate laid Esme down on a towel to change her. Esme was looking less and less like a newborn with each day. She could see John, Esme’s father, in her. His features were beginning to come through like a silicone mould, as if his face was slowly pushing through underneath.

‘Where am I?’ Cate said aloud. And Esme’s father smiled up at her. ‘Of course. The final insult.’

Esme whimpered. Her face softened and there Cate was. There I am, I see me. I am here, she thought. Esme’s eyes were slowly turning green—like Cate’s—flecked like the algae on the surface of a pond. She brought Esme to her chest, breathed in the scent of her soft hair. ‘I love you so much,’ she said. It was time for a feed.

While she fed her she worried. She worried about the failed attempt to get into town. She worried she had stepped out too far. She worried about the woman downstairs in the tie-dye dress: she worried she would come through the floor—somehow find her way up and in. She worried she was listening through the ceiling. The thought snagged—could she? She often heard things reverberating through the pipes—a gush and glug of water as a sink plug was pulled. A conversation somewhere. Sound reverberated across the courtyard. A thought struck her: she can hear me walking. She can hear every step I take. She knows where I am in the flat, she knows. Cate lifted a foot from the floor and placed it back very carefully, silently onto the rug. She knows when I’m doing my washing. She always knows. And she was always doing washing now—endless cycles—and the machine vibrates on the spin cycle on the floor. I can’t stop that from happening. And besides, she’ll see me hanging it out. There is nothing I can do about that.

Esme had fallen asleep, so Cate very carefully took her to the bedroom and placed her in the cot. She didn’t flinch or stir, just flopped like a rag-doll from her side to her belly. If Cate was lucky she would have a couple of hours peace. If she was lucky.

About an hour later she heard a quiet knock on her door. A soft tap—that of somebody who was nervous, tentatively knocking. Someone who knew there was a baby. Cate thought she could pretend she hadn’t heard. But the knocking continued.

Cate crept to the door and looked through the spyhole. She shrank at the sight. The woman just stood there waiting quietly. Perhaps she’ll just go away. If I do nothing she’ll go away. The woman came up close to the door and tilted her head sideways as if to listen. Cate took a step back, then looked through the spyhole again: the woman was still there, leaning against her door. She’s so close, if I open it, she’ll fall in. I don’t want her coming in but I’ve got to get rid of her. I don’t want her thinking she can just come up here whenever she pleases.

After an agonising minute of standing by the door holding her breath, she heard footsteps move away and down the corridor. She heard the door to the courtyard bang. The woman had gone to the courtyard. Cate moved to the window. The woman looked up at her, could she see through the net curtains? She didn’t think so. It was twilight but she had not put her lights on yet. The woman touched every piece of washing on Cate’s line, very carefully inspecting it. Cate watched, horrified, with her hand over her mouth trying not to let out a shriek. Then the woman in the tie-dye dress simply walked back inside.

Cate was on tenterhooks; she knew what was coming, she had been waiting all day and all night but nothing yet. Nothing yet. But it will. It will. While she waited she scrubbed the difficult stains from Esme’s clothes, she scrubbed the floors, she washed the door handles, she wiped the walls.

She’s not going away. She’s not going to go.

And there it was, the sound she had been waiting for: a quiet tap at the door.

This time Cate got right up against the door and after a few seconds quietly spoke, ‘Yes?’

‘There’s a leak.’

‘Oh?’ This was not what she was expecting her to say.

‘There’s a leak and I think it’s coming from your kitchen.’

Cate’s kitchen sink was blocked but she wasn’t going to say anything.

‘Can you open the door?’

‘I’ll call out maintenance tomorrow.’

‘Can you open the door?’

‘The baby is sleeping.’

Cate was afraid that opening the door to her neighbour would be misconstrued as an invitation to make friends. She did not want to make friends. Cate was afraid that the sanctity of her space would be ruined. Cate was afraid that whatever the woman brought with her would linger; Cate was afraid because the bedroom door was open and the baby might be woken up. Cate was afraid she no longer knew the difference between rational and irrational. The woman seemed ok, she seemed as though she wanted to help. She’s a neighbour, she’s just a neighbour. But those things she did to her washing Cate just couldn’t shake off.

‘I just want to show you—I think I know where it’s coming from. You can tell maintenance. I can help you.’ Her voice was friendlier than before, much sweeter. ‘I can probably fix it—it would save so much hassle. You don’t need the trouble, do you?’

Cate had heard that before. She flipped the latch. The door was now unlocked. She glanced through the spyhole again. The woman was a couple of feet away from the door. Waiting. Cate took a deep breath and pulled the door open. Her neighbour smiled. Cate noticed her hair was all dewy as though she had spritzed herself with a water spray.

‘Thank you. I know it’s difficult with a baby. But if I can just show you where I think the water is coming from.’

And before Cate knew what to say the woman had stepped across the threshold. She was in.

‘Oh,’ her neighbour said. ‘You’ve decorated really nicely.’ As she walked down the hallway towards the kitchen. Cate supposed that her flat was the same layout.

‘It’s coming from the kitchen,’ her neighbour said, going into the kitchen, ‘the sink, I think.’

‘It’s blocked,’ Cate blurted. ‘Look. I’ve got some stuff to put down it. I’ll do it tonight and hopefully that’ll clear the pipes.’ The sink was filled with dirty dishwater. Cate stuck her hand in and rummaged about to pull the bits of food from the plughole. As she raked about it glugged a bit, but the blockage didn’t budge.

‘I can call maintenance if you like. I know it’s hard—’

‘I doubt you do,’ Cate interjected. She knew what she was about to say and she didn’t want to hear it.

‘Cate, isn’t it?’

‘Yes.’

‘My name is—’ but Cate wasn’t listening. She didn’t hear her. The baby was crying. She must get to Esme.

She left the woman standing in her kitchen. Surely, Cate thought, this is her cue to leave.

She returned after a few moments with Esme all red faced and bundled up in her arms.

‘There she is,’ the woman said in a cooing voice. ‘Look at that sleepy little face.’

‘I need to settle her now so if you wouldn’t mind leaving us to it.’

Her neighbour’s face darkened to a shadow. ‘Do you mind not doing any washing until it’s sorted?’

Cate felt her cheeks flush with suppressed anger. ‘You’ll let yourself out,’ she said.

‘I’ll pop by tomorrow and see how you’re getting on.’

Cate didn’t reply.

Dirty washing was piled high in the corner of the kitchen floor when the maintenance man came by.

‘Amazing how fast it gets backed up when you’ve a baby in the house,’ he said cheerily as he fiddled about under the sink. The liquid sink unblocker had done nothing to help.

‘Aha!’ he exclaimed, ‘found the culprit.’

He held up some pieces of cloth: little arms and legs of a soggy, half eroded, torn up, faded, grime-covered, red sleepsuit.

‘What on Earth?’ Cate exclaimed.

‘Sleep deprivation can make you do the strangest things.’

‘I don’t know how I would have done that by mistake—or on purpose.’ Cate’s heart thudded in her chest. She thought back to yesterday: could she? But no, she’d left the neighbour in the kitchen for a few seconds, she wouldn’t have had time to plant it there. But Cate had left her front door unlocked sometimes, just to save time. There had been no reason to lock it whilst she was just downstairs hanging the washing.

‘Must be the previous tenant’s then,’ the maintenance man said, wiping his hands down and putting his tools back in the box. ‘She had a small baby too—just like you.’

‘Yes, that must be it. What a strange thing to do.’ But Cate didn’t really think that. She only thought of the woman downstairs, creeping about in her flat whilst Cate was outside, oblivious, hanging her washing out. She saw the wicked smile on the woman’s face as she slowly pushed the little arms and legs, the pieces of the sleepsuit through with the sharp end of a knife. Stabbing at it.

‘How odd,’ Cate said vaguely.

‘Yes indeed. Right, well, I’ll be off now. Give me a call if you have any more problems. Take care of yourself, love—it’s not easy.’

‘Thanks,’ Cate said and shut the door. There’s that line again: it’s not easy, it’s not easy, it’s not easy. Not when the bloody neighbour is fucking around. That’s what she’s doing, she’s fucking with me. Bitch, bitch, bitch. I know what she’s up to. I know what she’s doing.

But Cate didn’t know.

A couple of days later she passed the woman in the tie-dye dress in the hall.

‘I was expecting you. I fixed the leak. Did you notice?’ As Cate spoke she became angry—all those hours she had spent on edge listening out for the door, looking out the window, and the neighbour hadn’t even been bothered to check like she said she would.

‘Yes. Thank you.’ The woman in the tie-dye dress smiled, seeming not to notice Cate’s tone. ‘Did you find anything?’ She no longer seemed to care at all.

Cate was about to laugh a hearty sarcastic laugh. She was about to say, yes—of course I did. You know I did. But she stopped herself; she didn’t want the woman to think she was getting to her so instead she said a flat, ‘No.’

‘Oh. Must just have been food or something.’

She knows. She knows what I found because she put it there. But I’m not going to give her the satisfaction. Cate moved on up the stairs carrying Esme close to her chest.

‘Cate,’ the woman said, ‘have I upset you?’ She flashed a weak smile.

For a moment Cate saw herself fly at her, tearing the woman’s clothes, pushing her down the stairs; watching her tumble away onto the black concrete floor below. But she recovered her composure. Retreated from her murderous thought. What kind of mother thinks about these things with her baby in her arms?

‘Why would you think that?’

The woman shrugged, ‘I thought we might be friends. I think maybe my efforts to help have been misunderstood.’ Cate watched as her mouth closed around the word. She enunciated as though Cate needed a little help understanding her. Cate noticed her mouth had a shine to it: light pink lipstick shimmered as she spoke.

‘I don’t get much time for socialising I’m afraid so—’ Cate trailed off.

‘I love babies,’ the woman said strangely, desperately.

‘I’m doing fine on my own,’ Cate replied.

‘When was the last time you really slept?’

Cate was taken aback by this question. But Cate also didn’t know the answer. Nor would she say if she did.

‘I can help.’

‘I don’t want help,’ Cate snapped and turned and walked away.

‘You’d better bring your washing in soon!’ the woman in the tie-dye dress called after her. ‘It’s going to rain!’

Cate watched her neighbour from the window. She was wearing a puffy-sleeved dress this time and holding an empty basket as if she had just hung some washing; or was just about to collect some. She was starting to unpeg Cate and Esme’s clothes, removing them from the line. It was twilight, warm and still dry so there was no reason for this, none other than to completely rile Cate.

Cate couldn’t stand it any longer, she thought she might burst with rage. Doesn’t she have any of her own fucking clothes to hang out?

Cate banged on the window. The woman ignored her and carried on. Cate opened the window, leaned out and shouted, ‘Don’t you have any of your own fucking clothes? Leave them! Leave them! Leave us alone!’ The woman carried on as though she had not heard her.

With just a dressing gown on—and nothing on her feet—Cate gathered Esme up in her arms and fled the flat without even closing the door. She ran down the steps and out into the courtyard. But she was too late, the line was empty. Her neighbour must have the clothes but she had not seen her on the stairs.

She went back inside and down the corridor towards the woman’s flat. The door was ajar and she pushed it open with her elbow. ‘Hello, hello!’ she called. She heard nothing. But noted the flat was, as she’d thought, an exact replica of her own. She could have been standing in her own flat.

She pushed the living room door open. Her neighbour was sitting in an armchair exactly the same as hers with the bundle of clothes on her lap.

‘What are you doing?’ Cate screamed, clutching Esme close to her chest. ‘What are you doing with my washing?’

‘What do you mean?’

And then Cate saw. She saw a little rosy-cheeked face peeping out from the swaddling.

‘Esme,’ she said quietly.

‘No, Emma,’ the woman replied. ‘This is Emma.’

Loose clothing fell from Cate’s arms: babygrows, a little dress, a bonnet, socks and some of her underwear. The bundle she held was not her baby; it was nothing more than a bundle of her own damp washing.

‘You should have brought your washing in,’ the woman said with a smile.