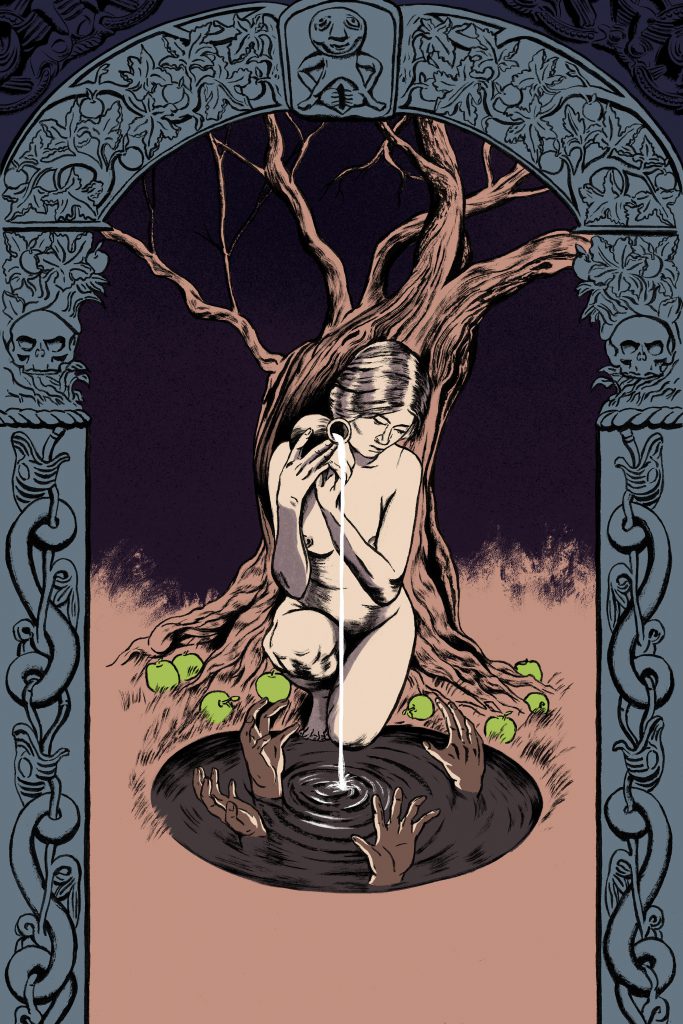

This Is My Body, Given For You

Heather Parry

Illustration by Joseph Gough

Content warning: Graphic bodily imagery and themes of sexual assault

Fermentation

No visitors, no letters, no laughing nor playing. They were children no longer; they were servants of God. They lived in cement cells with thin mattresses on the beds and cold water in the pipes. They had bible teachings all morning and work in the afternoon. They were looked after by twelve priests, all sour-faced and all with little patience for the young.

The girls had to learn to look after themselves. Self-sufficiency was key. They milled flour from locally-harvested wheat, churned cheese from local cows, made juice from the apples in their own orchard. They baked the thin wafers of the Body of Christ that they took in their mouths every morning at Mass as they knelt gingerly, their knees sore from crawling across stone, punishments given to make the girls learn the errors of their ways. The priests did not agree with spending money—not when the devil was waiting to make work for idle hands.

Lily, the new girl, was placed in the library, where her job was to neaten and tidy, to stack and arrange, to sit in a room alone and not cause any trouble. On the shelves, there were only books that taught the girls what they needed to know: how to grow food, how to feed others, how good women should behave. Lily made it her mission to devour every issue of the Farmer’s Almanac.

Lily had grown up with a baker mother and a farmer father. Her brother had learned to brew cider to support the family, and as a child she’d watched as each one perfected their craft. She spent hours with the almanacs filling the gaps in her knowledge, and soon she started visiting the kitchen after her library hours were over, teaching the other girls how to bake and brew and churn with skill, their knuckles rapped to bruises. They told each other how they’d arrived there, what sin they had committed to be sent away from home. They laughed and threw flour and were children once more, a brief respite from the rest of their existence.

As the girls in the kitchen improved under Lily’s tutelage, the priests commented that the bread was lighter and airier, that the cheese was smoother and more tart. Lily suggested that Mass would be more enjoyable if the Host was her own sourdough, sliced thinly so as to mimic the wafers. After tasting her toast, the priests agreed. Lily, gambling on better treatment for herself and for the others if she pandered to the men, told the priests that said she could make something else too, something that would ease the stress of their dutiful lives. They brought her an apple press and yeast and bottles, and they moved her responsibilities from the library to the kitchen.

Lily showed the girls how to make cider in barrels, forty litres at a time. She took the seeds from the apple pulp, washed them and saved them, every single one. She promised herself and the others that when the time came, when they were released, they would use them to plant their very own orchard, so they could make money and look after themselves. The cider was sweet and tangy and very alcoholic. The priests took to drinking in the evenings, and it turned their cruelty in a new direction. They stumbled in the darkness, all hands and shushing lips.

It started with just one of the priests, and it started with Lily. He took her in the nights, when the others could hear.

Life went on as it had. Lily still made the bread and churned the cheese and brewed the cider.

In the kitchen the next day, her mind turning, she took handfuls of apples from the cider pile and chewed them until she could chew them no more. She spat the matter into a metal jug and took another mouthful. She chewed and spat until her jaw ached. She juiced the pulp, covered it with a tea towel, set it aside from the rest of the cider, and went to bed to await her visitors.

By morning the process had already started. She added a little yeast and she went back day after day, but she waited. Her saliva sped up the process; after two weeks the special cider was ready. She could smell the alcoholic sweetness, could see the fermentation bubbles. She served it to the priests that night. They gulped it rather than sipped. It made them drunker than usual, and they came at her, this time in numbers.

But as they took her in the darkness, she thought: I am inside you.

Leaven

Lily grew sick, and then sore, and then larger by the day. She recognised the signs and said nothing. Her formless smocks covered her growing midriff, but as their hands slipped around her waist and onto her stomach at night, each one of them felt it. Each one broke a cold sweat and stopped, mumbling about the sanctity of human life and the indignity of fornication while pregnant. Each one, after a moment, continued.

She was not permitted to stop working. She kneaded the bread and churned the butter. She made the cider. The other girls helped as much as they could, but were shooed away by the priests and were beaten for trying. Lily passed eight months and could barely carry herself around the building, but if they saw her idle, they beat her.

While stirring the milk, Lily noticed wet patches on her chest. Her nipples, preparing for the child, were premature in their expulsion. Alone in the kitchen, she lifted her shirt and gently pressed her breasts; thin streams of watery-white liquid ran from both nipples, more freely than she’d imagined. She squeezed herself until no more would run, and she smiled as it dripped into the curdling milk in the pail. She stirred, watching it disappear into the mixture, and when she served the soft cheese up to the twelve priests, she had to turn away to keep from grinning. She was inside them.

The Rise

She squeezed and screamed and sweated out the baby in a bathroom on her own. None of the others were allowed inside, and the priests locked the door until the commotion was over. They gave her blankets and towels for it but refused further mention. The baby was a boy and she called it Grace.

It was three days until the priests started coming again. Her wet breasts, her ripe hips, the blood that would trickle from her after the act—they loved it all. Only when she grew sore and red, with white discharge leaking out and onto her underwear, did they change their methods. They spat in disgust and took her in her other orifices, where there was more pain but less trouble for them.

She was expected to work from a week after the birth, once she could settle the child and keep it quiet. The other girls crept into the kitchen to hold Grace when they could, and when none could come, Lily sat him on the counter, on the wheat sacks, on the cold floor, on her feet. She sifted and she churned and she brewed. Still her body grew more painful. She stopped drinking water because going to the toilet hurt so much her teeth tore into her cheeks. The mess in her underwear grew thicker and more yellow. Still the priests did not permit her to stop.

The solution came to her at night on a Friday, after their visits, when she lay awake both numb and alive with rage, the baby fastened to her breast, her hand stuck into her underwear to try and relieve the pain. She heard the screech of violation from the other room, the first time it had been anyone but her. She removed her fingers from inside herself and brought them up to shift the baby; she caught the sweet-sour, bready scent from beneath her nails, from the whiteish mess, and a voice spoke. She thought of the kitchen, of the oven. She lulled herself to sleep with the comforting thought of it, and the next morning she woke up feeling rested and alive.

She caught the other girls at their jobs, noting the dark circles around some of their eyes, the heaviness of their steps, and asked them to go and fetch some apples from the orchard. She took the baby to the kitchen and took the bread starter from its place on the shelf. She took a scoop of it and transferred it to a new bowl. With a chair against the door she slipped down her underwear and slid three fingers inside herself, the pain almost dropping her to the floor. When she drew them out, they were yellow-white. She took a wooden spoon and scraped the discharge into the starter, to which she added a little more flour and a little more water. She pulled up her underwear and left the mixture aside to grow. This part would bring her a bitter pleasure, but would not do what she needed it to do.

The girls brought her apples, as many as she’d asked for. She thanked them, kissing their cheeks, before sending them out of the kitchen, away from any blame. She peeled the apples, dicing them into small cubes, and set them on the stove in a thick pan with as much sugar as there was fruit. Setting the chair against the kitchen door once more, she retrieved her apple seeds from their hiding place, at the back of a dark cupboard at the far end of the room. By that time, there were three glass jars full of them—hundreds, perhaps thousands of the things. The girls had been saving them too. She had no time to count them, or to work out whether they’d be enough.

She put a jarful of the seeds into a hessian bag and smashed them to pieces with a rolling pin. Her arm strained with the weight but she kept going, kept going, until the seeds were no more, and in their place was a pile of rough, crushed, toxic apple-seed powder. Into the pan they went, stirred to combine, thickening the jam so much that she could barely move the spoon. She turned the heat off and poured into jars; it was golden orange with thousands of flecks of red, almost more seed than apple.

The bread starter was bubbling and full of air. She made a dough, folded it in, and left it overnight to rise.

By Sunday morning, it was brimming over the edges of the loaf pan, more active than she’d ever seen it before. She pushed it into the oven and spent the next twenty-five minutes feeding her baby, their baby, the one they’d all created.

The bread baked like a dream.

She cooled it and halved it and sliced it into thin, tongue-sized segments, crispy and tasty and perfect for a ceremony. She took twelve slices and placed them at the front of the communion tray, saving the rest for later. She delivered it to the priest in the usual manner, on the usual platter, and though it was thicker and differently shaped to their usual offerings, the smell of the freshly baked body was too much to refuse. As each of the twelve clergymen took their turns to kneel, they opened their mouths wide and the priest placed the bread from the front of the tray on their tongues. They each held it there, ecstatically savouring, letting the Lord himself melt into their mouths and seep into their systems, and she felt an excitement that tingled through her, that almost made her laugh. She served the rest of the bread to them later, loaded with the apple jam, topped with the soft cheese, with a glass of the fermented drink. They drank and she fed them more and more, until the jam jars were almost empty. They were full and delirious when they went to bed. A special evening treat.

Lily lay in bed, clutching Grace, waiting for the hour when the first of them would usually arrive. None came. She stared up at the ceiling until daybreak, then walked slowly, calmly to the priests’ quarters. She pushed open the door of the first bedroom. He was there, on his knees, pools of his own watery shit around him, blood streaming from his mouth and crotch, his hands clutching at his stomach and throat. Yellow-white discharge at the corners of his mouth. As the pain took him again he held his hand aloft, began shouting out the name of God, deliriously quoting verse, reality far from his finger. She checked all twelve rooms and they were all the same: white spots in the mouth, cracked lips, dry, split tongue, vicious incontinence, hemorrhaging from all orifices, screaming for their lives.

The noise brought down the rest of the girls. They stood, hands at their mouths, trembling, hardly daring to see what they were seeing, hardly believing. Lily pointed at the flecks of seed in the streams of vomit; she showed the girls the white mess at the men’s mouths. Gripping her swaddled child, Lily pulled up her dress and pushed her fingers inside herself again, to show them.